Four people were killed in a shooting at a Georgia high school on Wednesday, just weeks after classes began, and a 14-year-old suspect was taken into custody, law enforcement officials said. Jillian Kitchener produced this report.

The violence tore through Apalachee High School during the second month of classes, as students returned from a long holiday weekend. It was the deadliest U.S. school shooting of the year and the first since June, according to a database maintained by The Washington Post. Officials described a horrific scene on campus as they navigated the bloodshed in search of casualties.

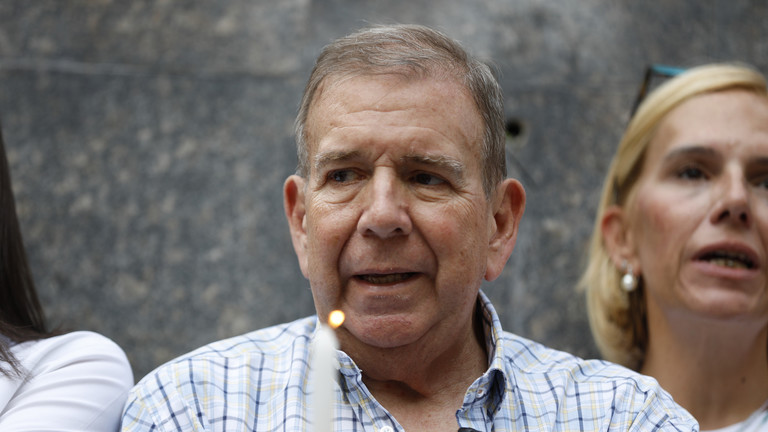

“We are still going classroom to classroom — and it’s a big high school — looking for bodies,” Kenny Cooper, the coroner for Barrow County, where Winder is located, said at midday. “It’s terrible. Please pray for us.”

The victims were identified as students Mason Schermerhorn and Christian Angulo, and teachers Richard Aspinwall, 39, and Christina Irimie, 53. No more fatalities are expected, Barrow County Sheriff Jud Smith said at a news conference Wednesday night. “All of our victims that are at the hospital are going to make it and going to recover well, as we’ve been told,” he said.

Winder now enters the annals of American communities forever scarred by mass gun violence, a national epidemic that unfolds everywhere from big cities to small towns. It is uniquely terrifying when it strikes a school, where students haunted by past high-profile shootings undergo repeated drills about how to survive if gunfire breaks out. In interviews Wednesday, students did not appear to be terribly surprised that the bloodshed had visited their campus.

It was “pure evil that happened today,” Smith said in emotional remarks at an afternoon news briefing. “My heart hurts for these kids. My heart hurts for our community. But I want to make it very clear that hate will not prevail in this county. I want that to be very clear and known.”,

Nearly 1,800 kids attend Apalachee, located in a rural area roughly 40 miles northeast of downtown Atlanta. The shooting brought the total number of students exposed to gun violence at school to more than 383,000 since 1999, according to The Post’s analysis.

Witnesses said they heard the first shots shortly after 10 a.m.

Stephen Kreyenbuhl was teaching a second-period history class when he got an alert about a school lockdown. Then, seconds later, he heard gunfire about four doors away: “Pop, then pause, then six shots, pop-pop-pop-pop-pop-pop.”

“My students were on the ground,” the 26-year-old said, his voice shaking. “Some crying, some consoling, some swearing.”

The evacuation was chaotic and surreal, Kreyenbuhl said, and as his class piled down the hallway after the lockdown ended, a grisly sight awaited them.

“It was terrible,” he said. “I saw a pool of blood when we passed [a] classroom where the shooting was.”

Police identified the suspect as Colt Gray, a student who attracted the attention of federal investigators more than a year ago, when they began receiving anonymous tips about someone threatening a school shooting.

The FBI referred the reports to local authorities, whose investigations led them to interview Gray and his father. The father told police that he had hunting guns in the house, but that his son did not have unsupervised access to them. Gray denied making the online threats, the FBI said, but officials still alerted area schools about him.

Authorities are investigating whether that incident — as well as contacts between Gray’s family and the local child services department — might be connected to Wednesday’s rampage, said Chris Hosey, director of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

Police recovered an AR-15-style rifle from the scene, he said, but they were still looking into how the suspect acquired the weapon and brought it into the school.

Hosey praised law enforcement’s “very, very swift” response, which he said spared many more lives. Within minutes of the first reported shots on Wednesday, police and two school resource officers confronted the suspect, and the young man immediately surrendered, Hosey said.

Apalachee High School staff had alerted authorities of an active-shooter threat Wednesday by pressing an emergency button on badges made by an Atlanta-based company, Centegix, Smith said Wednesday night. The company’s security system has been in use at the school for about a week, he added.

The suspect, if convicted, would be the youngest school shooter to kill more than one person on a K-12 campus in the past 25 years, according to The Post’s database. The attack — the nation’s deadliest since March 2023, when six were killed at a private Christian school in Nashville — is also the first deadly K-12 school shooting in Georgia since at least 1999, the year The Post’s database begins.

In her biology class, 10th-grader Abby Turner texted her mother to say the school was locked down. And it wasn’t a drill — she had heard the shots, too. Abby’s mother, Sonya Turner, asked where she was.

Abby wrote back: “i can’t explain it i’m shaking to much.”

Soon, Turner heard from her younger daughter, Isabella. Both were safe but terrified. In a group chat, they asked Turner what they should do.

“Pray….” she answered.

“I did. Like 8 times,” Isabella, 14, responded. Turner texted the words of the Lord’s Prayer — including the plea, deliver us from evil — and told them to keep trying.

“They said, ‘Mom, I’m scared,’” Turner said. “I said, ‘We’re coming, Dad’s coming, we’re coming.’”

When they made it outside, Abby met up with a friend whose teacher had been shot.

“When I found her, we were both crying,” Abby said. The friend, she noticed, had blood on her shoes.

All around them — at the Apalachee football field, which had turned into the family reunification point — first responders and parents swarmed.

Police closed the roads leading into the area, which also included two other schools that were placed on lockdown. Empty vehicles lined both sides of the main artery. Hundreds of cars were parked in ditches or abandoned on sidewalks in nearby neighborhoods. Unable to drive the remaining two miles because of police blockades, adults in tears ran to the school to check on their children.

As a television news helicopter circled above the football field, many parents appeared shaken, and most declined to comment as they left with their kids. Students appeared to form a prayer circle in the field as they waited to depart.

One approaching mother began to cry when she saw her young daughter. She ran to her, wrapping her in a tight embrace. Nearby, a boy pressed his mother for details about what had happened. “Did anyone die, Mom?” he asked. She walked briskly on and responded, “I don’t know.”

Sophie, a 15-year-old 10th-grader who declined to give her last name, was recounting the nightmarish experience to her mother, who had rushed to the school after receiving a message from her daughter that read, “My teachers shot.”

After hearing a loud noise, her teacher went into the hallway to check, Sophie said.

“We thought it was banging, but it was shooting. He ended up getting shot,” she said. There was “blood everywhere.”

As she listened to her daughter, Sophie’s mother, Emily, said: “I don’t have any emotions right now. It’s too surreal and devastating. Innocent people lost their lives today.”

Other students, in interviews, recounted how a normal day turned horrific. Suddenly, loud booms echoed across the building, they said, and a security alert advising a lockdown was posted on classroom video screens.

Doors in the school are set to automatically lock, but fearing someone might shoot their way into the room, students said they rushed to take cover in corners, while others crammed into a closet. In the chaos of the evacuation, many left everything behind, including their cellphones and car keys, so they borrowed classmates’ phones to call family.

Outside Winder, the response from state and national leaders followed a familiar pattern. President Joe Biden, who has long called for tighter gun-control measures such as a ban on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, said the shooting was “another horrific reminder of how gun violence continues to tear our communities apart.”

“Students across the country are learning how to duck and cover instead of how to read and write,” Biden said in a statement. “We cannot continue to accept this as normal.”

Georgia’s most prominent elected Democrat, Sen. Raphael G. Warnock, said the episode should galvanize support for bipartisan gun-control reforms in his home state and across the nation.

“The entire Winder community is in my prayers, but we can’t pray only with our lips — we must pray by taking action,” Warnock wrote on social media. Vice President Kamala Harris, likewise, called for action.

Meanwhile, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump released his own statement: “Our hearts are with the victims and loved ones of those affected by the tragic event in Winder, GA. These cherished children were taken from us far too soon by a sick and deranged monster.”

And Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp (R) said he would “make any and all resources available to help this community on this incredibly difficult day and in the days to come.”

At an evening news briefing near the school, Kemp added that “today is not the day for politics or policy.

“Today is a day for an investigation [and] to mourn these precious Georgians that we have lost,” he said.

Gun-control advocates consistently report that Georgia’s gun laws are among the nation’s weakest. The nonprofit group Everytown for Gun Safety ranks Georgia 46th in the country for gun law strength, in a tier of states referred to as “national failures.” The Giffords Law Center, another organization that advocates for stricter gun measures, gives Georgia an F rating on its annual scorecard, faulting the state for lacking rules such as universal background checks and red-flag laws.

During his term as governor, Kemp has expanded gun rights, including signing a 2022 bill that allows residents to carry a concealed handgun in public without a permit.

When Giffords delivered Georgia its failing grade, Kemp replied: “I’ll wear this ‘F’ as a badge of honor.”